Interactions with colleagues can be one of the most challenging aspects of medicine. The people you work with have a profound effect on how you practice – colleague interactions can lighten the burden, or make it infinitely heavier.

The experience of Medical Protection is that poor communications between two or more doctors, providing care to patients, lies at the basis or the heart of many complaints, claims and disciplinary actions.

It is inevitable at some point throughout your career as a doctor that you will come across at least one colleague who you have issues working with, it is therefore important to be aware of different strategies and techniques you can use to deal with the situation.

Clashes between colleagues often centre on attitudes, behaviours and skills in a colleague that challenge or are different to your own.

Some examples of common problems include illegible handwriting, another doctor interfering in your patient management plan, poor communication during handover, and colleagues who are slow to returns calls or emails.

So what can you do to reduce the risk around difficult colleague interactions?

-

Pick your battles

Use your energy wisely, you might have several issues with colleagues but some will generate more risk to patients and yourself than others. It is wise to concentrate your efforts and energy on high risk areas with the patients’ best interests at the centre of discussions.

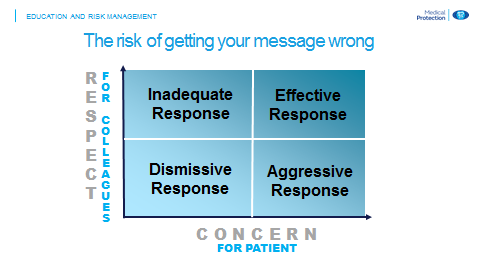

It is important to balance the amount of respect you show for your colleague along with your concern for your patient in order to get an effective response, as table 1 shows.

-

Catch and stop risky assumptions

Assumptions are a common, human error that we all make. They are especially prevalent when dealing with colleagues we dislike or find challenging. We can be more likely to make an assumption rather than check with that colleague. This generates a variety of risks that can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

The use of well-designed and mandated checklists or models to ensure completeness of communication can reduce this type of risk. Other effective methods to manage difficult colleagues include:

-

Handover

A standardised handover checklist, such as SBAR or SHIFT, which is trained, expected and policed, can cut through personalities. If colleagues don’t get along it doesn’t matter, an SBAR or a SHIFT is given and a patient is handed over safely.

MPS recommends the SHIFT method:

- Status of the patient

- History to this point

- Investigations pending

- Fears of what may unfold

- Treatment planned until care handed back

A useful addition to this is to check that the message has been received by asking the other doctor to repeat or read back what you have said. This can help with colleagues who struggle with attentive listening, or repeatedly fail to do what has been asked of them at handover. The ‘repeat back’ improves listening skills and checks that the message sent has been received and understood.

-

Actively manage disagreements

Frequently a ‘hint and hope’ approach fails to work. It can be much more effective to actively manage disagreements, however it is important to have the skills to do this the right way.

In Ireland you are required to have such skills. The Medical Council guide to ethical conduct[i] states that:

- Doctors should give professional support to each other

- Denigration of a colleague is never in the interest of patients and is to be avoided

- When disputes arise, they should be settled as speedily as possible and without undue publicity. Differences about clinical management are best aired without rancour in the appropriate settings

When addressing an issue with a colleague it is important to go in with respect and suggestions, otherwise they may feel backed into a corner. Any colleague who feels trapped is unlikely to behave well or engage in problem solving.

A good example of how to address an issue with a colleague is:

Edwina, I’m really concerned that the quality of communication between us is placing not just our patients but you and me at significant risk. Do you think we could allocate more time in the morning for clinical handover or perhaps use a checklist to help reduce our risk? I really believe we need to improve the way we communicate to help reduce the risk to us all. I am committed to doing this.

-

Escalate & Document

If you have a colleague who routinely puts you at risk you should consider:

- Raising your concerns directly with your colleague

- Suggesting options for how improvement could occur

- Framing the conversations in terms of the risks to all

- Highlight that you are committed to taking action

- Documenting your concerns and action taken

- Escalate to a senior/call Medical Protection if no resolution is possible

Make sure to record the steps you have taken to try and resolve the situation. It is important to have an evidence trail in these situations as they can end up in catastrophic outcomes for patients and doctors, including claims and referrals to the medical council.

CASE STUDY: We don’t talk anymore

Allowing personal rivalries and feuds to fester in the workplace is unprofessional in the first place; allowing them to interfere with the care of the patient is serious misconduct. This case highlights how such an incident didn’t just land the doctors involved before the GMC – it also landed them in court.

Mr Y, a 35-year-old marine engineer, was undergoing surgery in the posterior compartment of the thigh to treat a congenital vascular lesion. Mr O, consultant vascular surgeon, was carrying out the procedure. The lesion was closely related to the sciatic nerve and some of its branches, and Mr O was hoping to avoid damaging the sciatic bundle, if possible.

The anaesthetic was given by Dr A, consultant anaesthetist. During the induction phase Mr Y had suffered repeated generalised muscular spasms, so Dr A had given a muscle relaxant, to prevent intraoperative movement of the surgical field.

During the course of surgery, Mr O used tactile stimulation to attempt to determine whether a nerve which was likely to be compromised by his surgical approach was the sciatic nerve, or a branch of the peroneal nerve. Reassured by a lack of contraction of relevant muscle groups, he continued to operate under the impression that the structure about which he was concerned was not the sciatic nerve.

Unfortunately, in the context of neuromuscular blockade there was no rationale for this approach. It transpired that Mr Y suffered severe foot drop as a result of extensive damage to the sciatic nerve. Mr Y sued Mr O as a result of his injuries.

The case hinged on whether Mr O had taken sufficient care in establishing the relevant anatomy during surgery. Dr A had documented in the anaesthetic record that he had given the muscle relaxant, and was adamant that he had told Mr O this fact. Mr O was insistent that Dr A had not informed him about the administration of the drug and thus had left him open to the error that he made.

During an investigation of events surrounding the case it became clear that there was a history of animosity between the two clinicians. There were unresolved investigations into allegations of bullying and harassment between Mr O and Dr A. In the context of how Mr Y suffered his injury, and the clinicians’ apparent failure to communicate, it was impossible to defend the case, which was settled for a moderate sum with liability shared equally between the two doctors.

Medical Protection advice: It is a professional obligation of a doctor to, as the Medical Council says, “treat all healthcare workers, including healthcare students, with dignity and respect” and “ensure that there are clear lines of communication and systems of accountability in place among team members to protect patients”.[ii]

Effective communication between healthcare professionals is essential for safe patient care. In the context of an operating theatre, where there are anaesthetic factors that may have an impact on the surgical outcome (and vice versa), it is vital that this information is imparted.

Unresolved personal or professional disagreements between healthcare professionals who share responsibility for patients is potentially prejudicial to patient care. It is the responsibility of all who work in the clinical team, and those who manage them, to make sure that patients are protected from any adverse outcome that results from doctors not working properly together. The wellbeing of patients must always significantly outweigh the personal problems of doctors.

Independent, external professional assistance with conflict resolution may sometimes be necessary and can be extremely effective.

This case originally appeared in Casebook Vol 16 No 2, May 2008.

References

- Irish Medical Council 'A Guide to Ethical Conduct and Behaviour' 2004

- Ibid

Find out more