Receiving feedback can feel uncomfortable and it is often tough to hear about what you need to improve on. But feedback, good or bad, will be a major component of your career. Dr Lynelle Govender MBChB, PG Dip (HPE), MPhil (HPE) senior lecturer at the University of Cape Town, discusses the key ideas behind best feedback practice.

Feedback can be “one of the most powerful influences on learning and achievement”.1 While feedback can occur between peers, and across disciplinary boundaries. For the sake of this argument lets imagine feedback simply as conversation between someone who is ‘giving’ feedback and someone who is ‘receiving’ feedback. Let’s take a look at what you can do as the receiver of feedback to maximize its potential benefit.

"You're a medical student and you’re standing at the bedside. It feels more like you’re standing on the edge of a cliff. You can feel the eyes of the patient and the senior doctor watching you from the other side of the bed. Your hands are shaking as you’re about to insert an intravenous (IV) catheter for the first time; on a real, living, actual person. You manage to slide the cannula in, and see the tell-tale flashback of blood. Yes! You’re in!

Those shaky fingers though; when you try to connect the infusion tubing, a bit of blood spills. The senior who is supervising you doing the procedure observes quietly. The patient clicks their tongue irritably at you, annoyed at the sting of the needle and the bloody sheets. You secure the IV, and stop sweating for a moment. The senior watches the drip which is now steadily running, and then points carefully at the IV needle which you’ve forgotten to dispose of properly in the sharps bucket. Urgh.

The senior looks at you with something like pity or perhaps kindness, saying: “Come on, let’s have a chat about how that went.”

You drop the needle in the sharps bucket and gather yourself for the conversation to follow."

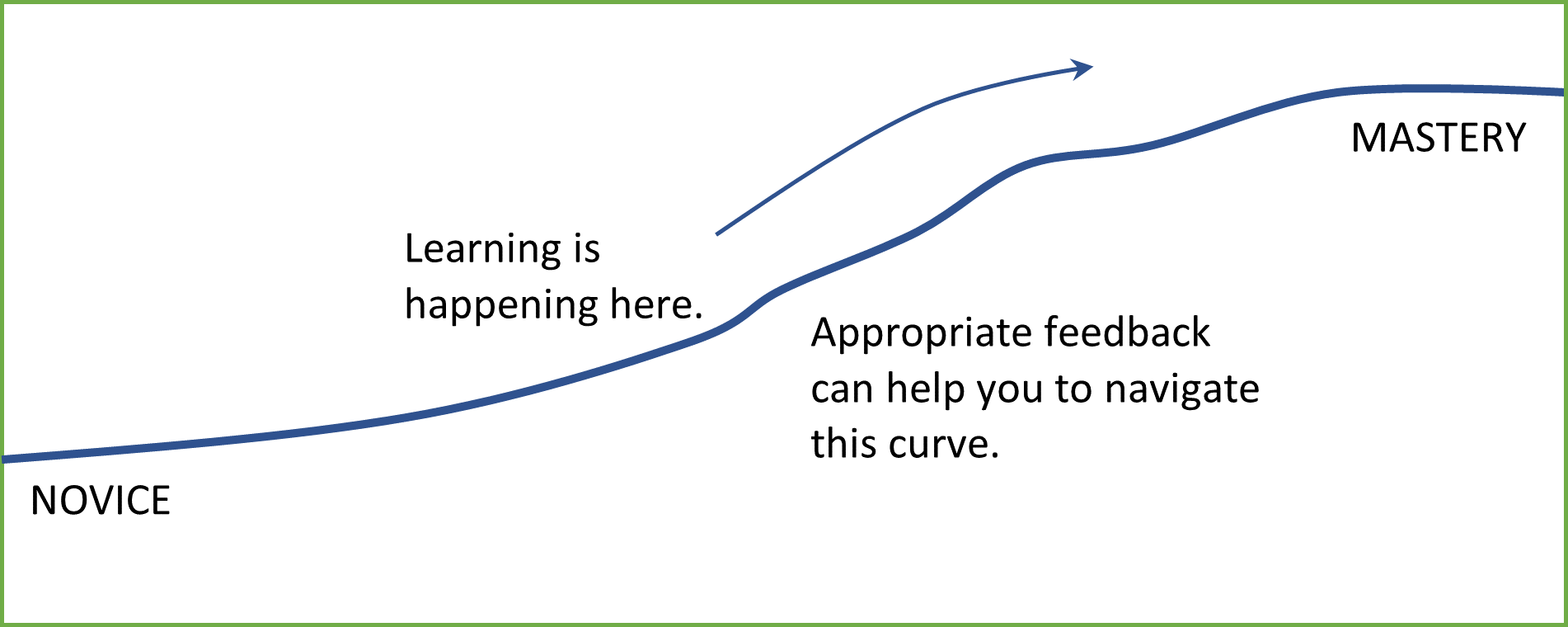

In some way or another, we’ve all been that medical student. At every stage in a doctor’s career there is learning to be had. Whether you’re an intern, or a registrar or consultant; at every level, everyone is learning. Every. Single. Day. This learning may take the form of new knowledge (for example: a differential diagnosis to a clinical set of problems), skills (for example: how to perform a cholecystectomy) or attitudes (for example: how to lead an entire department). Whatever the specifics of the learning may be, there is a point at where your level of expertise is currently, and a point where you would like it to be. Feedback can be an incredible tool used to bridge that gap; helping to narrow the distance between where you are, and where you are wanting/required to be.

So, what is feedback? The original definitions are mechanistic in origin. Machine loops rely on feedback to inform processes. As medical students, we’re taught something pretty similar when learning about the positive and negative feedback loops that play a role in human physiology. Simply put, feedback is nothing more or less than information, but how we understand that information has changed over the years.

In 1983, feedback was defined as “information describing students’ or house officers’ performance in a given task that is intended to guide their future performance in that same or in a related activity”.

2 30 years later it might seem like little has changed. Readers can likely relate to the experience of listening to a senior tell you how you went horribly wrong, and what you should do better next time. It’s not a wonderful place to be in. Feedback can be difficult to receive, particularly if the feedback is not particularly constructive. At times, it may seem like driving the feedback process is beyond your control as the ‘recipient’. But that’s not necessarily the way we should think about it, or the way it needs to be.

As medical education has evolved, there has been a key shift in the theory and practice of feedback. In more recent literature

3, this has been signalled by a move away from unidirectional feedback towards a bidirectional model. In simple terms, feedback isn’t a one-way street. It’s a two-way dialogue. What this means is that you don’t (necessarily) have to just stand there and listen to your senior speak, you can participate in the feedback conversation. In fact, you can lead the conversation and set your own goals. For example, as an intern consider speaking to one of your senior colleagues about where you would like your learning to go.

"I'm struggling with ECG interpretation, do you have a few minutes to help me please? Perhaps I can have a go at interpreting the ECG, and you can let me know what you think?"

See the difference? You don’t have to wait for feedback to come to you. You can seek feedback, you can direct the conversation and empower yourself by taking control of your own learning goals. Of course, this may be easier said than done. Whether a learner will actively engage in feedback dialogue may depend on individual learner beliefs and behaviours,

4,5 and whether the seniors and local context supports this kind of practice.

The take home messages for receivers of feedback are:

• Conduct an honest self-assessment, and try to figure out where your gaps are

• Build trusting relationships with your senior colleagues

• Seek feedback from colleagues who you trust and consider to be credible

• Create an action plan together with your senior to address your learning gaps

• Reflect on your learning and continue the cycle

These take-home messages may make it seem like it’s an endless loop of learning and feedback, and that might seem disheartening. But it shouldn’t be. Take comfort in the fact that wherever you are on your career path as a doctor, we are all learning. Learning to seek feedback, and accepting it with a growth mind-set may help to build an attitude of lifelong learning, which may benefit both you and the patients you serve.

In truth, each of us is in a position to both give and receive feedback. There is much that can be done to improve the way we give feedback and broader work required to shift institutional culture towards one that supports effective feedback dialogue 4,5. But that is a whole other kettle of fish, and probably worthy of an article on its own.

For deeper reading check out the useful resources below.

References

1Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of educational research, 77(1), 81-112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

2Ende, J. (1983). Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA, 250(6), 777-781. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026

3Ramani, S., Könings, K. D., Ginsburg, S., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2019a). Feedback redefined: Principles and practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(5), 744-749. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2

4Ramani, S., Könings, K. D., Ginsburg, S., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2019b). Meaningful feedback through a sociocultural lens. Medical Teacher, 41(12), 1342-1352. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2019.1656804

5Ramani, S., Post, S. E., Könings, K., Mann, K., Katz, J. T., & van der Vleuten, C. (2017). “It's Just Not the Culture”: A Qualitative Study Exploring Residents' Perceptions of the Impact of Institutional Culture on Feedback. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 29(2), 153-161. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1244014